RAS vs Traditional Aquaculture: Pros, Cons & Cost Comparison for the Canadian Market

For Canadian salmon farmers and investors, the choice between traditional open‑net pens and land‑based Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS) is no longer theoretical—it sits at the centre of regulatory change, climate risk, and long‑term profitability. This article explains how RAS compares with traditional aquaculture in Canada, focusing on performance, cost, and strategic fit in the Canadian context, supported by current data and official sources.

Why the Transition Matters Now

Canada’s salmon aquaculture industry is significant. British Columbia alone produced over 100,000 tonnes of farmed salmon in 2022, with Atlantic salmon representing nearly all of that output, so this transition is strategically significant for the sector. (gov.bc.ca)

Traditional Aquaculture (Open-Net Pens)

Traditional farming uses floating cages in coastal marine waters. It leverages Canada’s natural environment for oxygen and water exchange.

Advantages

- Lower upfront capital requirement compared to RAS.

- Established technology with decades of industry experience.

Risks

- Exposure to sea lice, pathogens, harmful algal blooms, and fluctuating ocean conditions (e.g., temperature changes).

- Regulatory pressure in key regions such as British Columbia due to environmental concerns. (Canada)

Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS)

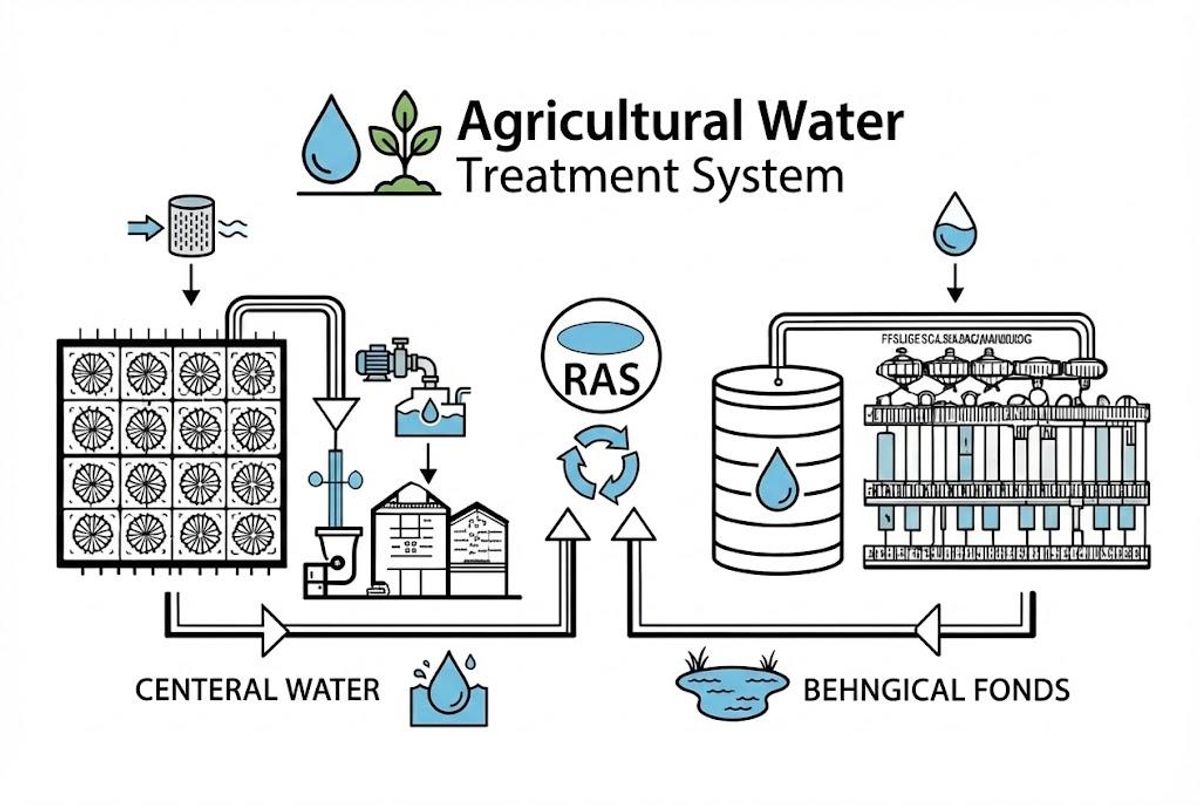

RAS is a land-based, closed-loop technology where water is filtered and reused.

Advantages

- Controlled environment reduces biological risk (e.g., parasites like sea lice).

- Enables farming inland or near major markets.

Risks

- High capital investment and complex engineering requirements.

- Energy demands are significantly higher than in open-net systems.

Detailed Comparison

Feature

Traditional Net-Pens

Land-Based RAS

Location

Coastal marine sites

Inland or coastal industrial

Regulatory Status (BC)

Phased out by 2029

Supported as a closed containment

Biosecurity

Higher exposure to environmental disease vectors

Highly controlled, lower disease risk

Feed Conversion (FCR)

~1.27 typical for net pen

~1.05–1.10 used in RAS models

Environmental Impact

Potential waste discharge into the marine environment

Waste can be captured and treated

Scalability Today

Proven at an industrial scale

Still emerging at scale

Notes on feed conversion ratio (FCR):The Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) analysis uses an FCR of ~1.27 for net pen salmon and ~1.05 for RAS scenarios in its financial models. (dfo-mpo.gc.ca)

Cost Analysis: The Financial Reality in Canada

1. Capital Expenditure (CAPEX)

RAS facilities require significantly more upfront investment than open-net pens. According to economic analyses of salmon aquaculture systems:

- RAS capital costs range widely due to scale and technology assumptions, generally from approximately USD/CAD $7 to $40 per kg of planned annual production capacity. (gov.bc.ca)

- This range reflects the lack of large-scale, steady-state RAS facilities in commercial operation and the use of model-based estimates.

- In contrast, net-pen capital costs are typically much lower per kg of capacity due to simpler infrastructure and use of natural water. Estimates from industry modeling place them below RAS on a per kg basis, although published numbers vary by context and design.

2. Operational Expenditure (OPEX)

Operating costs under RAS tend to be higher mainly due to energy use, additional labour, and system maintenance.

According to economic analyses of RAS technology:

- RAS operating costs (OPEX) are modeled in the range of roughly CAD $5.00 to $6.00 per kg of production output. (gov.bc.ca)

- These analyses highlight that feed, smolt (juvenile fish), and labour are the largest cost components, with energy for water movement and temperature control also significant.

Comparative Net-Pen OPEX:

- Published government technology assessments show net-pen operations have lower overall cost sensitivity, but do not provide a single universal per-kg OPEX figure for Canada. Industry models note significant exposure to environmental risk costs.

Feed Costs:Across systems, feed typically represents one of the largest operating cost categories; improvements in FCR reduce feed costs relative to output.

Strategic Considerations for Operators

When evaluating a transition from traditional net pens to RAS or other closed systems, Canadian producers should consider:

Regulatory Trajectory:

- BC’s policy clearly supports the shift to closed containment by 2029.

Energy Costs:

- Energy cost exposure varies by province; access to low-cost renewable power can improve RAS economics.

Market Premiums:

- Consumer demand for sustainably farmed seafood may enable price premiums for land-based products over time (qualitative industry trend).

Risk Tolerance:

- Open-net pens are exposed to environmental risks (e.g., sea lice, algal blooms), while RAS places greater emphasis on mechanical reliability and energy management.

Conclusion

Canada is at a pivotal point in its aquaculture development. The transition away from open-net salmon farming in British Columbia toward closed containment systems by 2029 is grounded in formal government policy.

Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (RAS) provide distinct environmental and biosecurity advantages and are supported by government direction, but they come with significantly higher capital and operating costs compared to traditional net pens — a reality reflected in recent economic analyses.

For producers and investors in Canada, understanding the true cost structures, regulatory incentives, and operational risks — grounded in verifiable data — is essential to making accurate long-term decisions.